Under the title Soffi (Breaths) various artworks made from 1977 onwards, through different materials and processes, are collected. All of them bring together experiences gained through previous works, especially those centered on the word and contact, and are based on a sort of transitive property, always linked to physical contact, in which facts, information and objective forms are transmitted from one element to another as part of the creation process, in their being part of nature.

Soffi (Breaths), 1975 (detail)

The breath is sculpture.

It is the sculpture of intrusive stone,

the growth of a branch,

a casting in bronze.

Breaths visualized with dust and photographed

are revealed as vase, drop, goatskin.

Some previous works show the convergence of language and sense of touch. In Pane alfabeto (Alphabet Bread, 1970), for example, a metal matrix with the sequence of the letters of the alphabet is inserted into a large bread dough, which Penone bakes and then exhibits outdoors. As birds peck at the bread, the letters of the alphabet are revealed.

Pane alfabeto (Alphabet Bread), 1970

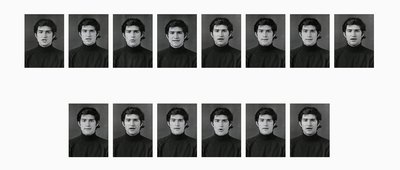

Alfabeto (Alphabet, 1970) is instead a sequence of twenty-one photos, each one showing Penone pronouncing one of the letters of the Latin alphabet. The same shots are combined differently, in alphabetical order or as to form the artist’s name and surname in a sequence that appeared in the manifesto for Aktionsraum 1 in Munich in 1970.

Alfabeto (Alphabet), 1970

The work Vaso (Vase), 1973-1977 is complex in elaboration and represents a turning point because the artist introduce materials and techniques that would be broadly used later on and he starts establishing a relationship with the past as a cultural fact, instead of only a natural one. The work consists of a vase from an archaeological excavation, on the surface of which the fingerprints of the ancient potter are visible. Four bronze elements complete it: they are enlargements of the traces pressed into the clay from the artisan's fingers, revealed by Penone through the casting technique.

Bronze is a noble and durable material. For the artist there is a correlation between the phases of its processing - with lost wax casting, in which the metal flows into the mould and the air is expelled from reeds - and breathing, such that the invention of the technique may have occurred at a time when man had an animistic conception of reality.

Vaso (Vase), 1975

The whirling rotating movement produced by the potter tends to facilitate in the clay the formation of a vortex, typically fluid form, readily filled by the intrusion of air that the potter, with the rapidity of his action, closes within it its vortex.

The exhalation of breath is equivalent to air that is introduced into the potter’s vortex, and it is equivalent to the word.

The word is extremely rich in connotations and is capable of arousing image that is, apparently, of creating from nothing.

Penone uses bronze for other well-known works, such as Patate (Potatoes, 1977) and Zucche (Squashes, 1978-1979). He makes anatomical plaster casts of his face and puts them in the earth where he cultivates vegetables; in this way, growing in contact with their cavities, the vegetables takes their shape. The entire process is documented photographically. Penone then selects five potatoes and four pumpkins grown according to his design and casts them in bronze. Details of the artist's face, mouth, ears and profile appear on the surface of the potatoes.

Patate (Potatoes), 1977

The squashes, instead, cast in bronze together with the bunches of flowers and leaves of the entire plant, show a deformed version of the artist's entire face. From the first exhibition during the solo show in 1978 at the Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, potatoes are always presented mixed with real tubers. Squashes, on the other hand, starting with a solo show at the InK, die Halle für internationale neue Kunst in Zurich, in the autumn of 1979, are exhibited together with Nero assoluto d’Africa (Absolute Black of Africa, 1978-1979), a block of granite in which Penone engraved an imprint of himself, to reinforce the contrast between expectation of durability of the materials chosen for the sculpture compared with the biological materials of the models.

Patate (Potatoes), 1977

Zucche (Pumpkins), 1978-1979

Nero assoluto d’Africa (Absolute Black of Africa), 1978-1979

For the Soffi series, much elaboration passes through the drawings, executed in earth colors, in sanguine, or using pencil, ocher ink or coffee, close to the tones of the terra-cotta material in which the pieces are modeled. In these drawings Penone records the volume that the air occupies inside the human body or the path it takes as it exits the lungs, when the breath is emitted from the lips, the shapes it takes when it does not encounter any obstacle, or when it brushes against objects, or the shapes it takes when it brushes against objects and the vortexes in which it frays. A meditation on Leonardo's works and Eastern graphics is explicit.

Soffi (Breaths), 1977

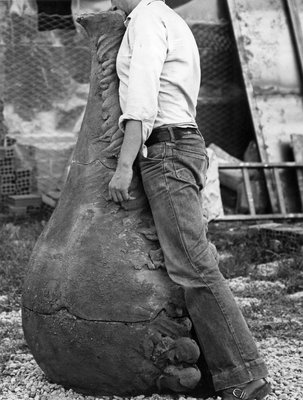

In the terra-cotta Soffi the artist gives material substance to the volume of his breath. He uses clay because it is "a solid element that has always been linked to fluids, with its plastic characteristics", as he writes in 1974. All these works have the approximate shape of a vase, which translates the primitive gesture of joining hands to drink, and evokes the womb.

Soffio (Breath), 1978

In the first phase of the creation Penone makes a plaster cast of the front part of his body, from neck to feet. Using a hand potting technique ("a colombino"), Penone superimposes clay, giving form to the curvilinear and drop-like direction of his breath, except for an axis along which the clay adheres to the positive of the plaster cast. In the upper part, where the diameter of the work is narrowed (that is, where the neck of the vase corresponds to the artist's neck), Penone presses the imprint of his face and inserts a clay cast of his mouth. The lips, sinking into the material, emit the breath, which thus materializes in the clay. In this artwork the artist arbitrarily intervenes, shaping what otherwise could not be seen, namely, the way in which the breath breaks up on impact with the body.

Giuseppe Penone with Soffio (Breath), 1978

In Soffio di foglie (Breath of Leaves, 1979), instead, Penone uses real leaves (boxwood leaves, replaced in another version with myrtle), which he piles up and then lies down on the pile, leaving a cast of his body and, turning his head to the side, exhales. When he gets up, the leaves record an imprint of both his body and his breath.

Soffio di foglie (Breath of Leaves), 1979

Breathing the shadow,

one’s own shadow;

the shadow of one’s own body extends inside,

to the entrails.

In Respirare l’ombra (To Breathe the Shadow, 1998) a conical shadow projected by the human body is obtained with a grid of bronze laurel leaves. The body that generates the flared form is suggested in negative, while the detail of lungs with the tracheal pipe is in all-round. It is created with a weave of laurel leaves cast in bronze as well, but it gleams with a gilded patina. Laurel is a mythological plant, gold is a mineral that human organism does not reject. There are strong relationships between the shadow of the foliage and the shadow inside the lung, between the leaves that produce oxygen and the lung that breathes it, between the cavity of the lungs and what is created in the casting process.

Respirare l’ombra (To Breathe the Shadow), 1998

In the 1999 exhibition at Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea in Santiago de Compostela (Spain), the walls of one of the rooms in the museum was covered with laurel leaves, held in metal grids. The scent of the leaves permeated the space, while the sculpture of a golden lung was hung on the wall at the height of an adult’s lungs. On this occasion the first book devoted exclusively to the artist’s writings, titled Respirar la sombra/ Respirare l’ombra, was published.

[See Daniela Lancioni, Soffi (Breaths), in Giuseppe Penone. The Inner Life of Forms, edited by Carlos Basualdo, Gagosian, New York 2018, booklet V]

Respirare l'ombra (To Breathe the Shadow), 2000

Soffio (Breath), 1978