The works of this series, as the ones of Reversing One's Eyes, convey reflections on identity. The focus is about what is traced in the skin, something that simultaneously delimits and separates. The skin as a sensitive surface, capable of relating with the world. In these works the primary source of knowledge is not the sight, but the action of contact, that is also identified as what the sculpture springs from. Contact is a knowledge that keeps on occurring spontaneously, and imprint is the result of the primary function of touch and a sign of identity.

The skin like the eye, is a boundary element, the end point capable of dividing and separating us from what surrounds us, the final point capable of physically enveloping enormous expanses…

It is the point that allows me, still and after all, to recognize myself.

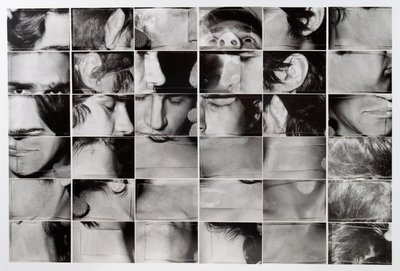

Svolgere la propria pelle (To Unroll One's Skin), 1970 (detail)

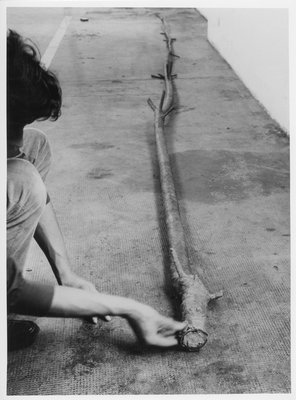

In a work such as Gli anni dell'albero più uno (The Years of the Tree Plus One, 1969), the collaboration between artist and nature is a process that takes place by exploring, touching and caressing the bark with fingertips to spread a layer of wax equivalent to a growth ring, according to the logic of the natural development. Here, Penone works on the trunk of a tree not through a process of subtraction, as happens with his debarked Trees, but by addition and his fingerprints coexist with those of the bark.

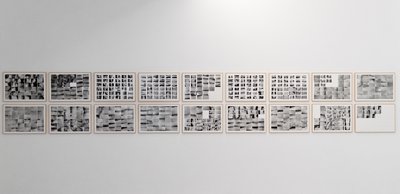

Another tactile exploration and creation procedure is frottage. As early as 1969, for example, he realizes Una lettura tattile della scorza dell’albero (A Tactile Reading of the Tree Bark), consisting in the detection of an entire trunk on fifteen sheets of paper rubbed with graphite. The same process, which uses the paper medium to establish a coherent relationship between the work and the page of the book, is often used by the artist when he is asked to represent his work in the catalogues of important exhibitions. For the exhibition Konception-conception at the Städtisches Museum Schloss Morsbroich in Leverkusen, he creates 8161 pagine di un libro (8161 Pages of a Book) by rubbing the same sentence engraved on a iron typographic matrix and on a wooden surface on five sheets of paper to represent the progressive assimilation of a text by a growing tree.

Gli anni dell'albero più uno (The Years of the Tree Plus One), 1969

Exploring various possibilities for "unrolling his skin", Penone experiments with materials and techniques such as ink, powder and adhesive tape to reveal the imprints of his skin, and photography with development and printing on transparent film. It is this film that the artist makes stick to, by "unrolling" his skin over them. With this procedure he creates Svolgere la propria pelle – finestra (To Unroll One’s Skin – Window), a series of works in which the property of the skin to be simultaneously an internal and external element finds correspondence in the window diaphragm. But the transparent films on which the skin detail is impressed can also be "unfolded" on handrails (Svolgere la propria pelle - ringhiera/ Unwind your skin - Handrail, 1970), as well as on the neon lights that illuminate the exhibition spaces (Svolgere la propria pelle - neon/ Unwind your skin - Neon, 1970). Svolgere la propria pelle - maniglia (To Unroll One’s Skin - handle), Svolgere la propria pelle contro l’aria (To Unroll One’s Skin against the air), Svolgere la propria pelle sui finestrini di un treno (To Unroll One’s Skin on the windows of a train), Svolgere la propria pelle sul pelo dell’acqua (To Unroll One’s Skin on the water surface) etc. develop the potential of the theme in further situations.

Svolgere la propria pelle – finestra (To Unroll One’s Skin – Window), 1970

By pressing laboratory slides on his own skin, the artist maps his entire body, documenting the process through 607 shots that, when assembled, become the photographic work Svolgere la propria pelle (1970) and then a book with the same title published by Gian Enzo Sperone in 1971. Penone carries out a similar inspection on the body of his dog Moretto (Svolgere la propria pelle - Cane/To Unroll One’s Skin - Dog, 1970).

In Svolgere la propria pelle – pietra (To Unroll One’s Skin - Stone, 1971) Penone takes a river stone, he touches it and then immerses it in acid. As in engraving processes, the acid corrodes the stone, except for the area of contact with the skin grease of the hand. The photographic sequence shows the action of Penone’s hand grasping the stone, the stone sinking into the shallow water, the water enveloping the stone and filling in the grooves made by the acid. The water makes the imprint of the hand visible and assigns a form and a material to the contact he has enacted.

Svolgere la propria pelle – pietra (To Unroll One’s Skin - Stone), 1971

In Svolgere la propria pelle su 41580 mm² (To Unroll One’s Skin over 41,580 mm², 1971), a fingerprint is repeated on 288 sheets that are equivalent to the area indicated in the title.

Svolgere la propria pelle – Dita (To Unroll One's Skin – Fingers) consists of ten photographs (one for each finger of the artist's hands) printed on transparent film and applied on reflective surfaces. One version is printed in black and white and another one in colour. Each of the ten photographs frames a different finger pressing on a transparent surface. At the pressure point the fingertip appears white, giving the mirror below the necessary transparency for refraction. The work was included in the first exhibition in Italy to give theoretical recognition to art photography, Combattimento per un'immagine, at the Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna in Turin, in 1973.

Svolgere la propria pelle – Dita (To Unroll One's Skin – Fingers), 1971

The work Guanti (Gloves, 1972) introduces the interest for the concepts of negative and positive that are inherent to the dynamic of contact. It consists of two photographs that show the right and left hands next to each other, palms exposed. In the first photograph the right hand is bare and the left hand has a latex glove, turned inside out, obtained from a cast of the other hand. The opposite action is shown in the second photograph. On each of the two hands the skin of the other hand "unrolls".

Guanti (Gloves), 1972

In Mano (Hand, 1972) a photographic image in colour of the artist’s hand is projected onto the plaster cast of his hand with the index finger pointing toward the viewer. The same technique of casting and projection is developed in works that investigate other anatomical parts, as in Guardare l’aria (To Look at Air, 1973), where the image of a model is projected onto a plaster cast obtained from the detail of the face with his eyes closed. Penone gets and exhibits a series of faces, involving his closest artist friends.

Guardare l’aria (To Look at Air), 1973

The pressure of the air on our body is the matrix of our skin.

A ray of light that strikes an object provokes the sensation

that pressure exists on the illuminated surface.

The pressure of light on the eyes.

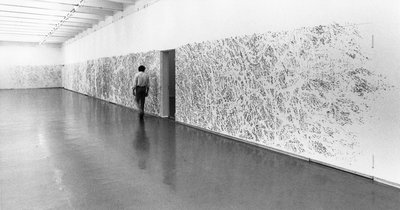

In Pressioni (Pressures, 1974-80) the imprint of the skin captured by transparent adhesive is projected on the wall at a greatly enlarged scale and then retraced in graphite. In these works the practice of enlargement is introduced, the logic of which can be traced back to the fact that touch, as Penone has observed, does not give immediate indications about the size of things.

Pressione (Pressure), 1977

Similarly, the works called Palpebre (Eyelids, from 1977) are enlarged imprints of the artist’s right and left eyelids. In most of these works, the drawings are complemented by plaster casts of the anatomical part from which they are taken. Penone suggests the possibility of seeing things simultaneously from the inside and the outside: "It's like looking through closed eyelids", he noted on the back of a photograph, as in Rovesciare i propri occhi (Reversing One’s Eyes).

Palpebre (Eyelids), 1989–1991

Everything unfolds on the surface, the entire life process is on the surface.

Clinging with your feet to the ground, and the head in the wind, in the sky.

Sloughing, debris, the residue that produces the humus necessary for life is of the surface.

The concern is to annul the debris, what isn’t alive,

to have only the present, the living, the actual in your eyes.

It is a concern that invests and requires enormous energy.

Man’s trace in nature is welcome,

it is received with serenity, it reassures us;

man’s trace in the city is something else.

You avoid it, look around with suspicion, it repels us,

it is continuously negated.

This is where most of the city’s activity lies.

There is disgust at the mere thought of a mark,

it is dirty, cannot be accepted,

it is essential to remove it, erase it, to create the space for a new stain,

sedimentation, evidence of experience that in turn will be removed.

The memory of man-matter is erased.

Form, instead, is extolled, matter to which man bears witness as thought,

better if with aseptic materials.

The dimension of a work of art will always be proportionate to the senses.

[See Daniela Lancioni, Svolgere la propria pelle (To Unroll One’s Skin), in Giuseppe Penone. The Inner Life of Forms, edited by Carlos Basualdo, Gagosian, New York 2018, booklet IV]

Svolgere la propria pelle (To Unroll One’s Skin), 1970