Absolutely central to Giuseppe Penone's research, the tree is the theme around which the series of the same name (Alberi / Trees), undertaken since the beginning of his career and still in progress today, is developed. In these works the natural material, changing over time and through the artist's action, takes on the appearance of an autonomous and lasting sculpture, capable of revealing a truth that is not metaphysical, but objective and indisputable.

To strip the tree layer by layer

from the weight of its gestures fixed in the wood,

to rediscover the moment of equilibrium

between the dimension of the wood and the form of the tree.

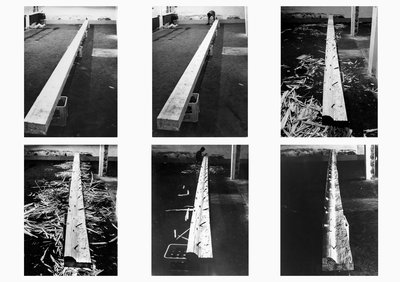

Giuseppe Penone working on Albero di 12 metri (12 Meters Tree) in Munich, 1970

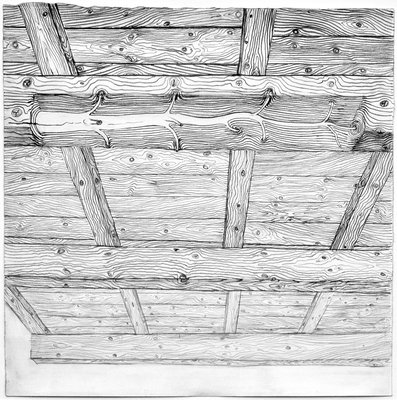

The idea comes from a reflection on the works and materials that have surrounded the artist since his first works at the end of the 1960s. Thinking back to the metal hand holding the ash tree trunk in Continuerà a crescere tranne che in quel punto (It Will Continue to Grow except at That Point. See Maritime Alps) and to the trunk that over time would have incorporated it, Penone senses that, if he could hypothetically bring it back to light at a later stage, he would regain the original contact of his hand with the tree; similarly, looking at some beams leaning against a wall, Penone notes that in the lines and knots visible on the surface, the growth rings of the wood and the sections of the branches of the plants from which they are made are recognizable: by excavating a beam it would therefore be possible to rediscover in it the shape of the original tree.

The realization process of the first trees comes from these observations. Penone chooses a beam in which the axial center of the trunk is visible, that is, the center of the concentric rings corresponding to the years of the tree’s life. Once he has identified one of the growth rings, he follows its profile and begins to dig into the wood. He barks the beam with the traditional tools of the carver: the mallet, the gouge, the chisel. When he meets knots, he digs around them, bringing to light portions of branches that had been incorporated into the trunk over the time. The beam is dug up to partially bring to light the plant, as it was in a moment before the hand of man or natural agents stopped its growth.

However, the tree is not completely extracted from the beam: an indication is left to suggest the process that generates the work. As the artist states, "If I had discovered the entire form of the tree, the work, from a conceptual viewpoint, would have been perfectly achieved, but there would have been no possibility of understanding it except through telling about it".

Gli alberi del tetto (The Trees of the Roof), 1970

The action of scraping a beam generates a double revelation. It brings to light the starting tree and also reveals the natural origin of many of the objects in our daily life. After observing one of these works, our ability to see increases in us: planks, floors, chairs, boats and any other similar artifact appear to us as what they originally were, trees.

The work embodies a tautology: it is a tree made from the wood of the tree itself, a sort of Ready-Made, but also an autonomous object and a visionary work. Again the artist expresses the rejection of an exclusive paternity of the work in favor of shared creation with nature; at the same time he expresses a critique of the standardization imposed by a society aimed at large-scale profit. Revealing a tree from an ordinary beam - identical to thousands of others on the market - and the skill that the process itself requires in the manual work of carving contrast with the repetitive and fragmentary production action of an assembly line - a hot topic while witnessing a widespread loss of practical knowledge and craft skills. Moreover, in the widespread trend towards dematerialization in works of art of that time, the tree has the quality of being an object, which Penone makes in large dimensions so that it is not interpreted as a piece of furniture.

Penone has repeated this action many times by creating many works and proposing them in different forms, as different are the forms in nature. In this sense, Trees are an exploration of the notion of identity. The complexity and depth of the title attributed to one of the first works, dated 1969, Il suo essere nel ventiduesimo anno di età in un’ora fantastica (His Being in the Twenty-Second Year of His Age in a Fantastic Hour) demonstrates this.

Giuseppe Penone, Albero di 4 metri (4 Meters Tree), 1969

To gather together in a single space the forest of trees discovered in the wood is to recreate the interweaving of the social relationships existing among the individual trees of the forest and the secret contacts of their roots, the mixing, the union, the intimacy that the idea of the wild suggests.

Rise, trees of the woods and of the forests, rise, trees of the orchards, of the avenues, gardens and parks, rise from the wood which you have formed and bring us once again the memory of your lives, tell us about the events, the seasons, the contacts of your existence.

Take us once again to the forests, to the darkness, shadow and scent of the underwood, to the wonder of the cathedral which is born in the forests.

The potential of Trees is explored in many ways by Penone. They were exhibited for the first time in Turin, at the Gian Enzo Sperone Gallery in 1969.

In the first versions, a segment of trunk emerges along the entire surface of the beam, with a high relief effect. These Trees called orizzontali (horizontal) are set up diagonally, leaning against the floor and propped up on the wall, or positioned on the ground.

Other Trees vertically disposed (Alberi verticali / Vertical Trees) date to 1979–80. They are obtained from square section beams, and emerge in the round, with the exception of one end of the beam, which is left rough, and acts as a support so they are standing sculptures. This typology includes Albero di 12 metri (12-meter Tree), dated 1980, which was placed for an exhibition in 1982 under the dome of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. A different Albero di 12 metri now in the collection of the Tate Modern in London, is composed of two elements carved from the same beam, placed side by side to balance each other: in the element corresponding to the lower part of the tree, the raw beam coincides with the base of the trunk; in the other, which corresponds to the upper part of the trunk, the raw base is the top of the original tree.

Ripetere il bosco (To Repeat the Forest), 1969-1997

During the second half of the 1980s Penone created Alberi elicoidali (Helical Trees). In this series the beam that is left exposed, turns around the carved trunk like a helix, as if it is under a torsion process.

In another variation, the Alberi libro (Book Trees), the trunk emerges from within two oblique surfaces of the beam, like the pages of a book.

From the solo show at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1980 Penone started juxtaposing some Trees under the title Ripetere il bosco (To Repeat the Forest) and he re-proposed the installation from time to time with variations. As in the installation studied for the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, in 2007-2008, where both the faces of the trunks are revealed with variation along the axis of the beam.

Ripetere il bosco (To Repeat the Forest), 1969-2004

In the series Nel legno (Into the Wood), Penone intensifies the sense of variation and randomness and, moreover, the intermediate phases of the work are visible, with the result that the design and the unfinished work make the affinity between beam and tree more evident.

Albero porta (Door Tree), first created in 1993, still develops other concepts. In the large trunk of a redwood tree Penone digs a door, an empty space of measures suitable for the passage of an individual, and inside finds the slender stem of the young plant. Cedro di Versailles (Cedar of Versailles), is a similar work, on a centuries-old tree that fell in the forest of the castle during a storm in December 1999.

[See Daniela Lancioni, Alberi (Trees), in Giuseppe Penone. The Inner Life of Forms, edited by Carlos Basualdo, Gagosian, New York 2018, booklet II]

Giuseppe Penone working on Cedro di Versailles (Cedar of Versailles) in his studio, 2000