In the 1980s Giuseppe Penone dedicates himself completely to sculpture, using traditional materials (wax, wood, plaster, earth, bronze, stone, marble). The awareness of the "extreme precariousness of the concept of solid, fluid, hard, soft, positive, negative" guides the artist’s investigation in intercepting forms and making revelations about the state of matter or its dynamics of transformation.

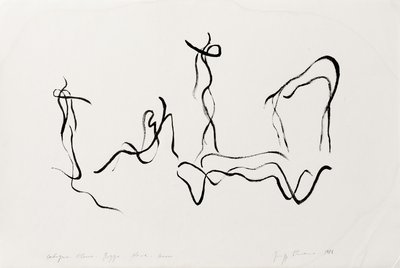

While in Essere fiume (To Be a River) this changing reality is faced by repeating the work of nature, with Gesti vegetali (Vegetal Gestures) the key to the sculptural process is the possibility of fossilizing a movement.

Gesto vegetale (Vegetal Gesture), 1986

Among the works that prelude this series, there are the Cocci (Shards, 1979). After having explored the shape of the vase in a homonym series in 1975, in this case Penone combines fragments of ancient vases with the primordial gesture of joining hands to contain water. The artist holds a ceramic shard in his hand, drips liquid plaster into their hollow and makes it solidify. Once hardened, the plaster adheres to the fragment and, at the same time, takes the imprint of the artist's hands.

Later, in 2004, Penone returns to repeat the gesture by inaugurating the series Geometria nelle mani (Geometry in Hands), in which the fragments of the vase in his hands were replaced by toy geometric solids (a circle, an oval, a square, a triangle, a trapezoid). It is the photographic negative instead of the plaster that documents the gesture, and it also reverses the darkness into light and the full into void, eliminating the difference that separates them.The following year these works with geometric solids held in the hands become matrices to create five large-scale sculptures. Bronze replaces plaster and the solids are made of contrasting reflective steel. Inside the solids, a gap opens up to allow a glimpse of the mold from which the sculptures are made, with life-size fingers providing a clue to interpreting the work and an attempt to suggest the common origin of seemingly opposing elements, macro and micro, positive and negative.

Cocci (Shards), 1979

Geometria nelle mani (Geometry in Hands), 2004

In 1979 the cup-shaded hand gesture inspires a series of works of vertical development, called Albero d’acqua (Water Tree). They are columns formed by overlapping casts obtained by pouring liquid plaster into cup-shaped hands. The relationship between this verticality and that of the human figure is well explained in a drawing, in which a "plaster column" rises from a small vase placed on the ground, ending in an element similar to the spout of an amphora, identified as a "shard". Next to the column, Penone places the silhouette of an individual in the act of drinking from a shard. As the artist writes, "the condition of sculpture is verticality" and "raising water is a poetic moment (...). The condition of water is formless, the condition of sculpture is form. Giving form to water is a poetic moment. (...) To raise water in order to drink it is a vital necessity, to visualize this event is to construct something that is similar to us".

In the vertical group Albero d’acqua e Soffio di foglie ( Water Tree and Breath of Leaves, 1980), Penone combines two different works, inserting a bronze Breath of Leaves into the column of a Tree of Water, at the height of an adult's mouth.

Albero d’acqua e Soffio di foglie ( Water Tree and Breath of Leaves), 1980

Impressing a rotating movement on the chin that grasps and holds,

and to the lip that licks and pours, one obtains a vase.

In 1979-1980 Penone is in Mönchengladbach (Germany) for an artist's residency at the Abteiberg Museum. The works of the period have a sensuality that is only alluded to in other works; female and male genitalia are inverted, corresponding to each other and reveal their similarity to plants. The origin of these pieces can be found in Zappa di terra (Hoe of Earth, 1980), a work made with a tree trunk from a forest near Mönchengladbach, and a clay element in which the artist fossilized his hoeing gesture. At the highest point of the gesture, the artist sink the blade of the hoe into the clay, leaving only the handle visible, which suggests the connection between the nature of the tree and that of the man-made instrument. In this work the rapid gesture of the hoe is associated with the slow growth of the trees.

Zappa di terra (Hoe of Earth), 1980

Zappa e vasi (Hoe and Vases), 1980

In a later work, however, Zappa e vasi (Hoe and Vases, 1980), the gesture is an iron plate, the extension of the blade of the hoe, and touches a row of terracotta vases, flattened against each other until they overturn (like the earth overturned by the hoe). The action of the hoe that fertilizes the earth is juxtaposed to the shape of the vase, traditionally associated with the womb, thus creating a link between "coltura" (cultivation) and "cultura" (culture), two words that have a common etymology.

An economy of gestures produces the sculpture, turning vertiginously around a point gives the concentration of space necessary for sculpture.

I rest against the form that spirals with its concentric lines in the space and in the material.

It is the need to avoid friction, which holds back the wind of action, to give the sculpture, the animal gesture of the vertical tree, the vegetal gesture of the sculptor.

Around the tree’s gesture the sculptor’s action is dispersed and in the sculptor’s vegetal gesture the tree’s action is held.

Around the sculpture

around the sculptor

boxwood, laurel, myrtle, olive.

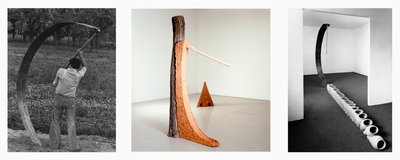

Gesti vegetali (Vegetal Gestures), 1984

The first drawings relating to the Gesti vegetali sculptures dates back to that moment and contains a proposal to "Build a giant leaf the size of a man", as "The plant is a sculptor in the repetition of its gestures that, established and superimposed, produce its presence in space". The first Vegetal Gesture in bronze is a female body outlined from a life-size mannequin. Penone outlines the gestures with clay, leaving his imprints on the material. From the clay he makes bronze castings. This work has been repeated in different shapes and installations over the time.

Studio per gesti vegetali (Study for Vegetal Gestures), 1984

In some of the earliest Gesti vegetali, the bronzes are juxtaposed with a forked branch, also seen in a 1982 work titled Biforcazione (Bifurcation). In Doppio gesto vegetale (Double Vegetal Gesture) from the same year, the bronze gesture of a leg is conjoined with a forked branch held up by the fossilized gesture of an axe. In some Gesti vegetali — exhibited in solo shows in 1982 and 1983 at Konrad Fischer in Zurich, at the Durand-Dessert Gallery in Paris, and at the Christian Stein Gallery in Milan — the bronzes are juxtaposed in accordance with the logic behind their execution, thus reinstating the human figure, albeit partially. All the subsequent Vegetal Gestures are hollow figures traced by a single gesture, or group of gestures that are executed in sequence, revealing the figure.

Gesti vegetali (Vegetal Gestures), 1983

The choice to use bronze is motivated by the fact that it is the material that allows to get closer to the appearance of a tree trunk. In 1980 Penone wrote: "In bronze, plant-life preserves all of its appearance and, if placed in the open, it reacts with the climate, oxidizing and thus taking on the same colors as the plants which surround it. Its patina is the synthesis of the landscape". And about the meaning of fossilizing a gesture, "that have developed in a space", the artist says that it "brings man closer to plants, forced to live eternally beneath the weight of the ‘gestures’ of their experiences." It is significant that the gestures in question are ordinary. "With gestures that are taken for granted, real, normal, there is a toughening of the heroic spirit of the work of art, an example of the sacred banal that lies within things".

Sentiero (Path), 1986

Sometimes well-known images from art history are taken as a model by Penone to create the Gestures, such as a medieval bas-relief of Eve of the in Autun cathedral (Gesto vegetale – Eva di Autun/ Vegetal Gesture – Eve in Autun, 1983) or an odalisque by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Impronta vegetale/ Vegetal Footprint, 1982). In Grande gesto vegetale (Big Vegetal Gesture, 1983), a single figure is held upright from the ground by three extended "gestures", and the empty space that these create evokes an absent base. The faces in these sculptures are shaped from a squash leaf cast in bronze. In Sentiero (Path, 1983 and 1983-1984), which exists in various versions, a solitary figure proceeds solemnly in the space, leaving a trace of its path.

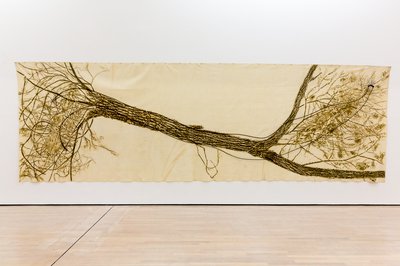

Verde del bosco (Forest Green), 1986

Generally, the Vegetable Gestures have been exhibited outdoors with plants filling the hollows and blending with the human figure, or indoors, together with potted plants. The gesture entitled Paesaggio Verticale (Vertical Landscape, 1984), showed at Castello di Rivoli in December 1984, rises above a vase filled with earth, but instead of plants, the hollow figure is crossed by a canvas on which the forms of trees and foliage are impressed. This creates an almost natural link with Verde del bosco, a series of frottages obtained by rubbing leaves on tree bark.

[See Daniela Lancioni, Gesti vegetali (Vegetal Gestures), in Giuseppe Penone. The Inner Life of Forms, edited by Carlos Basualdo, Gagosian, New York 2018, booklet VII]

Le radici del verde del bosco (The Roots Of The Forest Green), 1987